A cliched formula for determining a cyclist’s ideal number of bicycles:

n + 1

Where n is the number of bikes currently in possession.

Like most jokes, this one is often all too real. Despite being rabidly anti-consumption, I found myself caught in the trap. At my lowest point, I had a stable of ¡6! bikes. 6 bikes is reasonable if you have a road bike, a mountain bike, a beater for town, a triathlon bike, etc., provided you have a use for each of them. In my case, all but one (pic above) were essentially the same thing – old mountain bikes. The only mitigating factor was that all were second-hand.

I try to convince myself that I had a decent reason for such excess. Here goes!

I’ve been into backpacking for much of my adult life, taking every opportunity to embark on backcountry jaunts. I’ve enjoyed riding bikes since I was a kid, but had never gone beyond daily bike commuting and occasional single track. I yearned for more – I was inspired by a friend who regularly travels real distances (automobile-scale) on his bike, and by others who have undertaken long-term bike travel.

In early 2019, I finally read about something that had become popular over the past decade – bikepacking. It combines the most appealing aspects of backpacking and biking: backcountry jaunting and covering long distances. I immediately became obsessed with building a bikepacking machine.

I could have spent thousands of dollars on a modern bicycle designed for bikepacking. I’m not sure if I’m anti-consumption because I’m cheap, or cheap because I’m anti-consumption, or if the two traits are totally independent, but that distinction is academic. My priority was to do this for the least cash, with as few new parts as possible. I knew that a nice steel mountain bike frame from the 90’s would more than suffice.

Pre-COVID19, bargains abounded on Craigslist. People were always cleaning out their garages and selling beautiful vintage bikes as scrap. The only catch was that they often required some TLC. I had three simple requirements:

- High quality cromoly steel (True Temper, Tange, Columbus, etc.);

- 1 1/8″ headtube so that I could use a semi-modern threadless fork;

- My size.

Finding this ~1996 Jamis Diablo was a huge dopamine rush. The original owner, who had long ago upgraded to modern mountain bikes, sold it to me for a song.

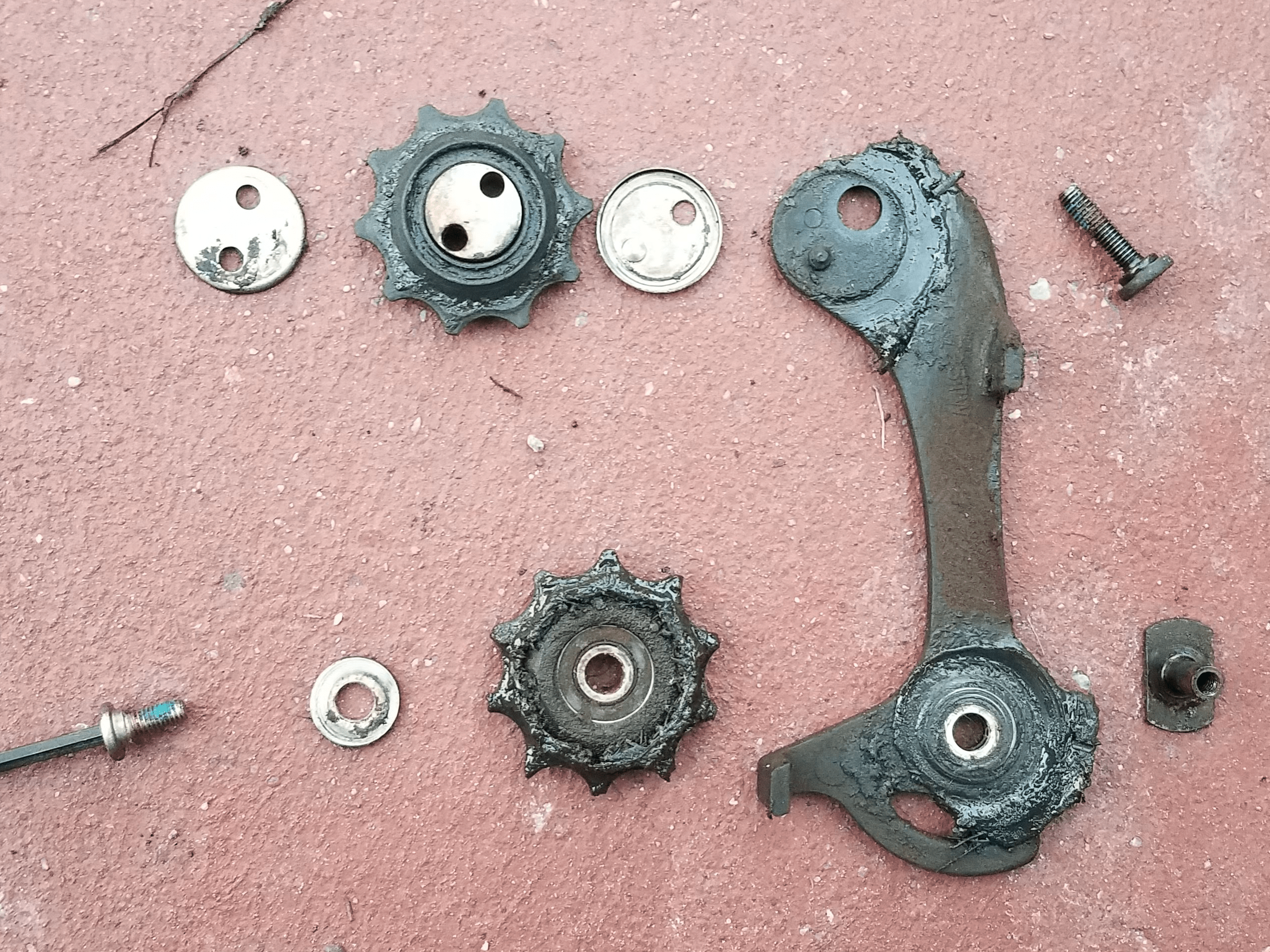

Vintage “wooden” derailleur; exploded for cleaning and jockey wheel replacement

It was rideable, just barely. I replaced the rear derailleur jockey pulleys, replaced the cassette and chain, replaced shift and brake cables/housing, dialed in the shifting and braking, and installed new tubes. I had to spend hours watching Youtube videos and failing (aka “learning”) because the only thing I had done correctly in the past was replacing tubes. I also deep-cleaned everything and sanded, primed and painted all scuffs and scratches on the frame to prevent rust.

After what must have been tens of hours of learning and labor, I was ready for the final step – replacing the suspension fork with rigid. I knew exactly what I needed: a rigid steel fork with threadless steerer, at least 7″ steerer length, and both rim and disc brake mounts. After months of scouring Craigslist, an amazing deal appeared and, miraculously, I was the first in line. In case I had missed something, I brought my old fork to compare with the seller’s. To my astonishment, the steerer diameters were different. Mine was slightly smaller!

I left empty-handed. On the way home, I slapped myself; I should’ve bought the fork anyway. It could be useful, and worst-case scenario, I’d sell it for a profit. But it was too late – sold. There’s a Chinese saying for these situations – “交了學費”, which approximately means “let it go, it’s a tuition fee for learning that lesson”. It was a cascade of failure. Ignorance, complacency, lazy due diligence, all that time cleaning and painting the frame, the cost of all those replacement components, and , to top it off, choking at the buzzer and missing the most remarkable Craigslist find of my life.

Turns out my ignorance wasn’t utterly inexcusable. 1″ threadless forks are rare in the realm of mountain bikes. ~95% of the time, 1″ forks are threaded and 1 1/8″ forks are threadless. Anticipating that it would be difficult to hunt down an ideal 1″ threadless fork, I decided to cut my losses, set the Diablo aside, and renew the search.

To be continued…

Useful resources:

- Bikepacking.com

- Park Tool Youtube Channel

- RJ the Bike Guy Youtube Channel

- Sheldon Brown